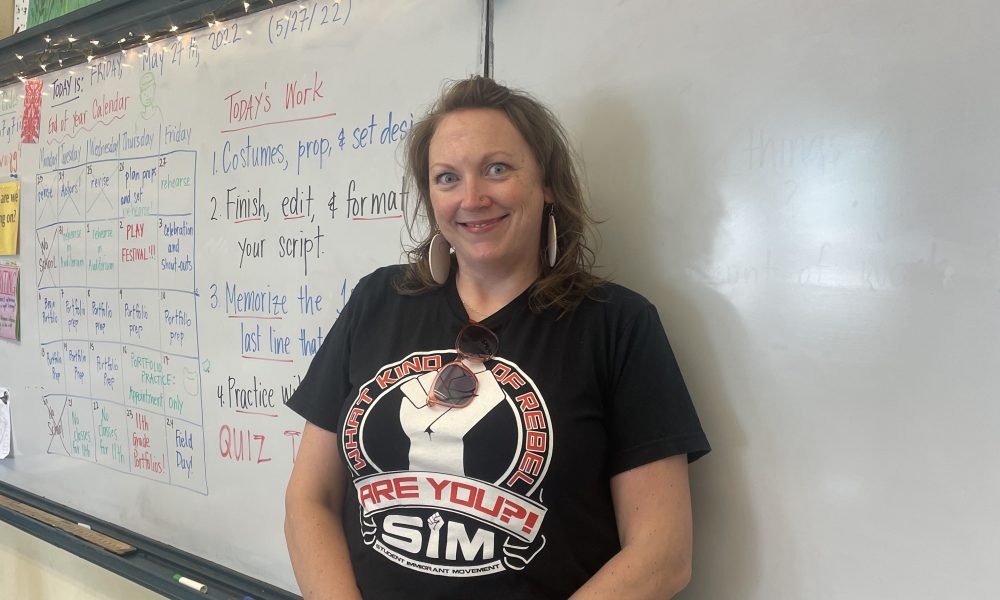

Emily Bhatnagar, 18, is one of today’s leading youth philanthropists in the United States.

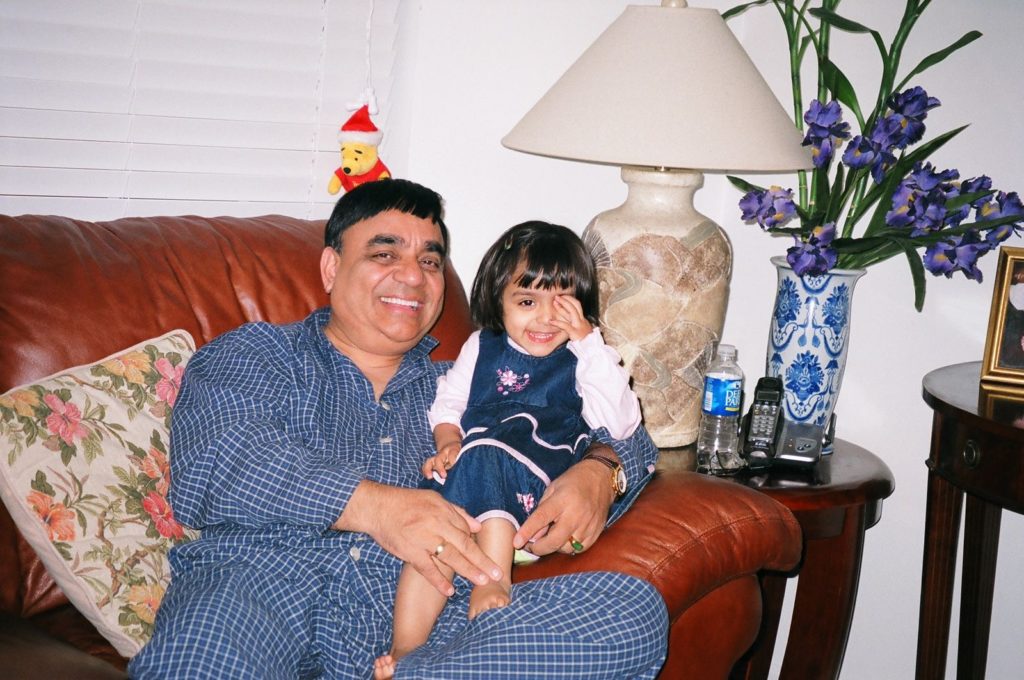

After Bhatnagar witnessed her father (whom she calls her “best friend”) nearly lose his battle with stage four thyroid cancer on her 16th birthday, she began developing severe trauma responses. Between Bhatnagar’s increased responsibilities at her family’s small Indian bread shop, tube-feeding her father during her ten-minute breaks between virtual classes, monitoring his medical needs, and taking over finance for the family business as she prepared to be listed as her father’s beneficiary, she became very ill for months due to exhaustion and was hospitalized.

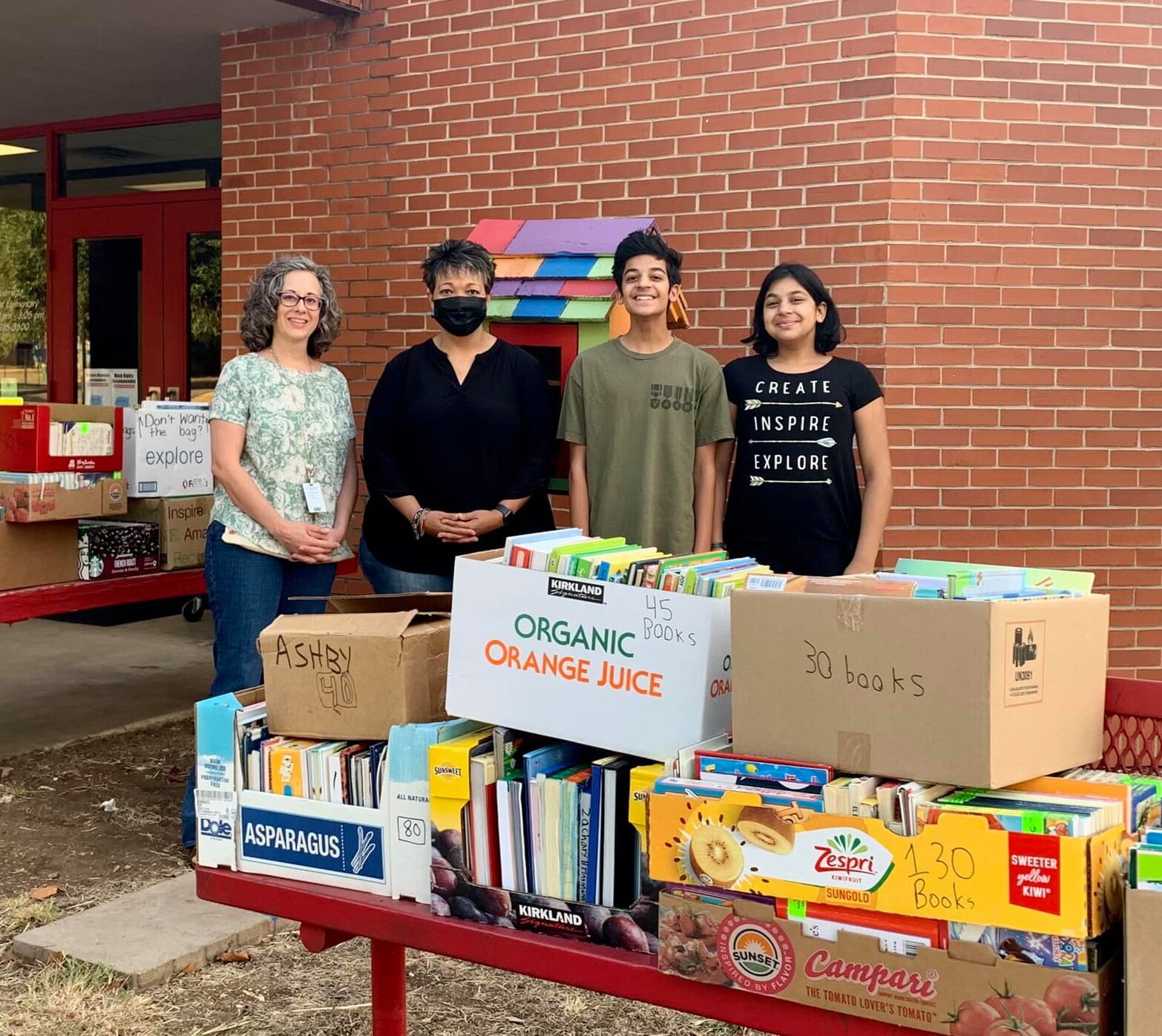

Months later came the birth of For Love & Buttercup: a book-drive initiative Bhatnagar began to spread hope by gifting books to children undergoing cancer treatment. A long-time bibliophile herself, Bhatnagar has since donated tens of thousands of books to hospitals while garnering mass public attention for her story.

Below are some words Emily shared with us as she reflects on her story as a first-generation American:

When I was in elementary school, I remember there was an enchanting maple tree by the schoolyard that touched the periwinkle-violet sky of summer dreams. It was gentle, wise. As if the ensemble of dancing leaves each had a voice of their own, they whistled and swayed to the choreography of the rain-kissed east coastern wind. Don’t be shy, they said, don’t be shy. Repeat after me: “May I please play with you?” And so off I went, skipping, stumbling, staggering, until I would feel that pesky lump in my throat and scurry back to the maple tree in my mulch-filled sandals all over again. They didn’t want to play with a brown girl, after all.

The maple tree was my favorite spot to hide from the other kids at recess, to gaze at soft, sugar-spun clouds of cotton candy and silently giggle at Papa’s attempt to sing me Oh My Darling, Clementine on the nights he wiped my tears and tried to cheer me up from the mean things my bullies would say to me. “Just listen, she can’t even pronounce the number three,” I would hear them whisper over the sound of my own heart thumping as twenty-four pairs of eyes waited for me to answer the question in my soft Indian accent. “Is she like–poor?”

And so every three o’clock as the school bus dropped me off and the marigold haze of golden hour sprinkled onto the fireflies that came out every May, Papa would hold me in his arms for hours and hours until the moon shone and stars scattered across the Maryland night sky. I would tell him all of it—about the kids who called me “Butt Booger” to make fun of my ethnic last name, about the maple tree, about the towering fences that surrounded the maple tree and how I sometimes thought about climbing over the fences and running away until I found the rundown chickadee picket sign that stood outside my home. “You’re my brave girl. If I let you stay home with me today, what about tomorrow? And the next?” my father would always tell me with a soft smile as tears rolled down my cheeks, our foreheads touching in agreement as my little round glasses clinked with his ones.

I couldn’t run away, but I could hide under the covers of big picture books I found in the colorful library of my kindergarten class. It was then I fell in love with words for it was through reading I lived a thousand, extraordinary lives. In one of them, I was a mighty sailor of the deep blue ocean with vows to find treasure and in another, I was a ballerina twirling in a snow globe under Parisian moonlight. As I grew up, to magically transport to a madly mythical, magnificent world where my father wasn’t dying of cancer was an antidote I held dearly to during the times I forgot the sound of my own laughter.

It was in the autumn of 2019 when the air was brisk and the town rust-colored when Papa was first diagnosed with stage four thyroid cancer. Still, under dim hospital lighting and thermal blankets, he smiled. Made jokes. He told me to be a brave girl, go to school every day, and take care of Mama. And then one day, he stopped breathing.

Though little glimpses come to visit me in my dreams every now and then, I can’t remember much of that night because I try not to think of it. But what I do remember is that Papa was rushed to the hospital at dark and the head surgeon came in in his pajamas to perform an emergency tracheotomy on my father. I remember the nurses telling Mama that his cancer had just “spread too far,” and I remember my brother making sure I ate more than a few bites of my sandwich each day we waited at the hospital.

Someone once told me, “It is with love alone we can keep someone alive longer than they would have otherwise.” I know that to be true because I saw my papa again. Though he permanently lost his sweet voice in the process, I can still hear him singing Oh My Darling, Clementine to his five-year-old girl as he picked her up to reach for the faraway stars in the night sky. It’s just now, his heart takes front stage.

Papa spent the next few months undergoing radiation treatment. Just like the fictional characters I had met in between the pages of these tales, I, too, had begun weaving dreams as my father so bravely continued to battle cancer. I dreamed of healing, of sending heaps and heaps of bundles of love to children who told themselves they were outcasts. But to do that, I first had to be brave enough to “draw my own box” and paint it dripping with melanin.

I’m eighteen years old now. As I sit under the maple tree thirteen years later writing the words to my very first essay to be published, I realize just how special it is to be that shade in-between. I have never felt American enough, nor have I ever felt Asian enough. It’s gray. To feel gray is quite okay and lovely, actually. It isn’t lonely like I thought it would be. I have friends. There’s charcoal gray, graphite gray, flint gray, and fog gray, just to name a few. And as you head more toward the right you’ll find that there’s silver gray—a dashing combination of just the right amount of goodness and, of course, dark, as there naturally is in most every situation—and then, cloud gray, melting with a beautiful shiny luster train of pastel galactic tints. All of these variations—all of these binding experiences, people—they feel the same way I do and hold on to the same rope. They’re gray. We’re gray. Together. If you ever feel like you don’t belong in your world, I promise what you’re seeing is just one little fragment of a mosaic waiting for you to find a reflection of yourself in one of its equally brilliant and brilliantly one-of-kind pieces.

*I would like to dedicate this piece to the only person I think would ever quite understand the inner workings of my mind, my sweet father. When I was little, I used to pray every night whispering, “Please, please, please send me a very best friend!” It was my biggest wish in the whole wide world, and I would cross my fingers until they turned pale because I thought the tighter I crossed them, the more likely it would be for it to come true. It’s funny because I didn’t realize that my tooth fairy wishes for all these years had already been granted the day I was born—it was my sweet, funny, kind immigrant papa with his big endearing nose and soft, glistening doe eyes all along. I think the greatest compliment I can ever receive is when someone says I remind them of you. I love you, Papa.