Our Executive Director, Maya Enista Smith, had the immense privilege of speaking with Dr. Nadine Burke Harris — the first Surgeon General of California. In addition to her role as Surgeon General, Dr. Burke Harris is a pediatrician, a loving mother of four, and has spent decades researching the impacts of Adverse Childhood Experiences, or ACEs, on health and development.

Check out the interview below as Maya and Dr. Burke Harris talk about how early adversity impacts our mental health, how we can break the cycle of trauma with kindness and compassion, and what resources are available if you or a loved one is living with ACEs.

. . .

Encourage a culture of kindness and compassion within your community by pledging to#BeKind21.

. . .

Maya: Your research on ACEs has shown that children who experience four or more ACEs are 12.2 times as likely to attempt suicide. I’d love to hear some examples of ACEs, and how they interact with our mental health.

Dr. Burke Harris: The term ACEs comes from research that was done by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Kaiser Permanente. They looked at 10 categories of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), such as experiencing physical, emotional, or sexual abuse; experiencing neglect; witnessing domestic violence; or having a parent who is substance-dependent or incarcerated. The research showed a very strong connection between ACEs and mental health. The more ACEs a person experiences in their childhood, the greater the risk of serious mental and physical health conditions, such as suicidality, depression, substance use, or dependency — but also seemingly unrelated things like asthma or diabetes, and long-term health problems.

Maya: So here in California, we are two and a half weeks back into the 2021-2022 school year. I’d love to hear some of the ways that schools and communities can practice kindness to address toxic stress in parents and youth who’ve experienced ACEs. What role can kindness and other stress-buffering activities play in both people who have both children and parents who’ve been experiencing ACEs?

Dr. Burke Harris: Kindness has a powerful effect on our brains and bodies; it’s deeply healing. Research shows that lifelong stress and trauma are not a prescribed fate for people who have lived through ACEs. We can overcome these challenges through consistent, safe, stable, and nurturing relationships and environments — having someone see you, understand you, say that they care about you, and take a moment to connect with you.

There are other scientifically proven interventions for practicing self-kindness, such as getting regular exercise, practicing mindfulness and meditative breathing, and just tuning in to how our body feels. Globally, we have all been experiencing one of the biggest stressors we’ve seen in a generation; and around the world, childhood and adolescent anxiety and depression have doubled. There’s never been a more important time for parents, teachers, and our community to practice kindness and support for ourselves and others.

Maya: Absolutely. I feel like you’re talking directly to me. So you mentioned taking care of our mental health as a way of taking care of our kids’ mental health – we know from our own research at BTWF that young people are aware of their parent’s mental health, whether their parents choose to share it or not. It’s something that young people are astute enough to pick up on their parent’s mood and influence their own. In what ways can we incorporate kindness in the household to help foster a healthy parent-child relationship at home?

Dr. Burke Harris: As a pediatrician, I tell guardians the most important ingredient for a healthy child is a healthy parent. As Surgeon General, I tell community members that self-care is not selfish; we have to put our own oxygen masks on in order to be of most help to our children.

Image courtesy of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

Image courtesy of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

There was a moment during the height of COVID where my eight-year-old looked at me and said, “You know, Momma, it looks like you’ve lost your giggle.” It was this powerful reminder of how important it is for me to support and sustain my own emotional well-being; my kid knew I was struggling and he was affected. We often, especially as parents, give to everyone else first, right? And we deplete ourselves. It is just such a good reminder that it’s okay for me to practice self-care and it’s okay for me to take a moment because it’s an important investment in the wellbeing of my entire family.

Maya: Absolutely. One of the findings in our research was that young people didn’t feel safe telling their parents when they were struggling because their parents didn’t share their struggles with them. So, for young people that have experienced toxic stress from ACEs, how can we go about healing and finding solutions that work for their mental health?

Dr. Burke Harris: One important piece is finding a person who you trust, who you can connect to, whether it is a parent, a coach, a therapist, a rabbi or an auntie. Find someone in your life who has your back, who understands what you’re going through, who cares about you, and who can create a space where you can be vulnerable and share what is the real deal that’s going on with you. Developing these trusted relationships is incredibly important. The good news is that having just one trusted ally is enough to make a difference in someone’s health and wellbeing.

Maya: Having one caring person in your life is also a huge protective factor against suicide. We talked about self-care as a must-have. What are some of the ways you recommend that young people who are living with toxic stress or impacted by ACEs go about practicing self-kindness?

Dr. Burke Harris: One tool that I love is called “Touch, Shake, Breathe,” and it’s based on the science of what helps our bodies feel grounded. Some of the exercises use sensory techniques of touching something solid, focusing on how it feels, and being attentive to what that experience is like. When we’re triggered, it can be helpful to connect to our bodies and the world by integrating the use of our senses: by touching, smelling aromatherapy scents, shaking it out, dancing, or anything else that helps your body refocus itself. Mindful breathing can also work wonders. When we calm down and focus on our breathing, it activates the part of our brain and our nervous system that counteracts the fight or flight response. Physical exercise can also help. The next time you feel upset, go for a walk outside. This will burn up some of those stress hormones and release the healthy hormones that help our bodies be able to cope when we are in those extremely challenging moments. There are other great suggestions and resources for recentering and getting reconnected to your body at NumberStory.org, a site specifically focused on identifying and overcoming ACEs.

Maya: Absolutely. And just adding to that, however folks are feeling at and in this moment is okay. I am fortunate enough to be the daughter of a psychoanalyst, so my therapy and talking about my feelings carries no stigma, but for many folks, therapy’s not as accessible or socially acceptable. So from a healthcare systems perspective, how can systems and communities work to de-stigmatize and make treatment more accessible?

Dr. Burke Harris: One of the silver linings of this pandemic is that people have become more aware of how common mental health struggles are and how important it is for folks to have accessible, affordable resources. Here in California, we just invested in a $4 billion initiative to build out comprehensive mental and behavioral health for children and youth. I want that type of plan in every single state — real robust investments to ensure that mental and behavioral healthcare is accessible in schools and that someone seeking mental health care can get it from a professional who looks like them and speaks their language.

The COVID pandemic has also presented an opportunity for us to establish new systems and break down roadblocks. Just about every therapist I know is now conducting phone visits, Zoom visits, FaceTime visits. I think that there’s a lot of exciting work happening right now around increasing accessibility and acceptability. Additionally, my office is developing a trauma-informed training for teachers so that every educator can understand how to identify and support young people who are struggling.

Image courtesy of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

Image courtesy of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

Maya: I love that. At the Foundation, we work with an organization called Find Your Anchor, and together, we created this campaign called “Please Stay.” It’s an incredible campaign that we’re very proud of, rooted in this idea that anchors are the things that keep you here in the world. I’d love to hear from you, just some of the examples that you have on what your anchors are? What’s keeping you in the world on the hard days?

Dr. Burke Harris: My kids, for sure. There is nothing more important to me in my life than making sure that my kids feel loved. Even on my worst days, I know that I need to be here just to love my kids.

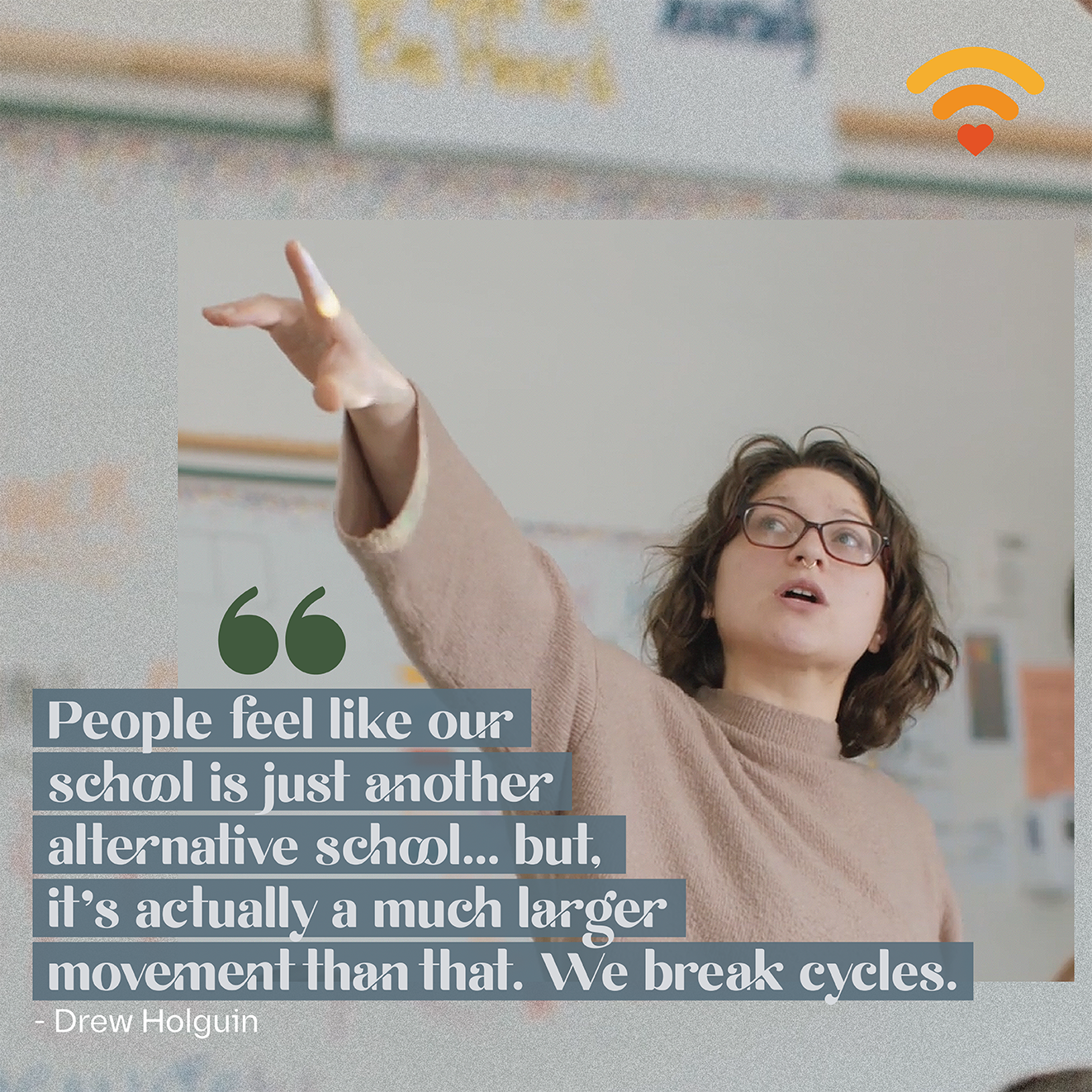

Maya: I want to talk about the cycle of ACEs, so there’s a lot of emotions to unravel when addressing ACEs. I’d imagine a child who experiences ACEs may blame their parents. The parents also have experienced ACEs, and then there’s a cycle that’s created. How can kindness and empathy play a role in breaking this cycle?

Dr. Burke Harris: Kindness can absolutely help us break the cycle, and kindness for ourselves might be most important. One thing I see time and again is how hard it is for adults, especially those of us with ACEs, to feel that we might be doing anything harmful to our kids. We know what that hurt feels like. We don’t want to revisit it and we don’t want to think that we might be perpetuating that cycle.

Despite our wishes, ignoring the trauma doesn’t help us overcome it or avoid inflicting it on our children. But, what if we speak to ourselves about our ACEs and residual feelings with that same voice, the same forgiveness, the same concern that we would for someone we love? If we offer ourselves that care and forgiveness, ACEs have the power to be our superhero origin story. They can motivate us to do things differently than the generation before. We can look inward and say, “Wow, my dad was really angry, and sometimes my temper gets the best of me too. When that happens, I am not a terrible person. I am having a common response for someone who’s been through what I’ve been through. But, I can forgive myself, and I can make a better choice going forward. I have the power to determine the next chapter of my life, and to shape my children’s stories for the better.”

Maya: Are there any other resources that you want us to share either for youth who think they’ve experienced or are experiencing ACEs and want to learn how to get support or adults looking for tools and strategies to support themselves and their children?

Dr. Burke Harris: In addition to NumberStory.org, which is fantastic for adults who are looking for resources, AcesAware.org has a ton of resources for health professionals. Another awesome resource is a five-part television series, The Me You Can’t See, which talks about mental health. And then, of course, for anyone in California, there’s CalHOPE!

Maya: I’m so grateful for your time today. I want to give you a minute for anything else you want to put in there for our readers.

Dr. Burke Harris: I’ve been doing this work over the past decade and a half, and one of the biggest challenges has been the sense that we can’t heal from childhood trauma — that if we were messed up then, we’re messed up forever. That’s just not true. It is never too late to begin healing. There is so much that we can do in our own lives, whether it’s talking to doctors and therapists, or practicing daily self-care rituals. Equally important, we must recognize the work that we can do as a society to support each other – how we vote, how we engage, how we participate, how we get active about things. These things make a difference — a big difference. I am profoundly hopeful that these incredibly challenging times are a catalyst for all of us to recognize how important it is for us to practice kindness and care for ourselves and others; that we can make a huge difference; that healing is possible. I believe that deeply to my core.